It was rather enchanting, how I died. I was hovering above their heads when they wrote with a blue bic ballpoint pen that it was from natural causes. But I am certain it wasn’t that. We never just die from the cause; other things mark the real ending. And even then, it’s not quiet a real, nor a final, ending. I turned 82 a week before that death paper certified me dead.

I was never married, but I was once engaged in my 30’s. We met in a science convention in a suburban town in Cairo called Maadi. I used to be a lawyer there whose clients were distressed women seeking revenge from their husbands by leaving them altogether. I was considered a feminist by default, because women had to always be the victims for me to make money.

In other most common words, I managed to make the destruction of families quick and easy, irrespective of the truth. I had known my fiancé for six months only. He had a striking chiseled face and top-notch ego. He made a living by spending hours of silence watching birds and writing about them in scientific journals.

He was the only man who loved me enough to be able to loathe me just as much, and the only man who destined me to permanently reside on the fine line separating two roads: one of being loved and powerless, and the other of being powerful and lonely. Need I tell you which road my eyes were fixated on, and which road I defied my nature for? Be that as it may, it was a rewarding place to be.

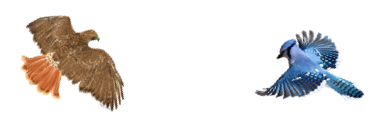

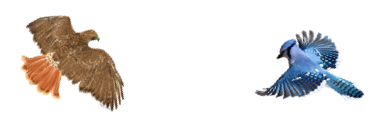

The last thing he said to me, my birdwatching lover, was something that I thought was redundantly pathetic back then. He said, “You are a typical pretty blue jay bird squawking like a hawk.” And then he kicked the table that had on it the blue jay vase made of Murano glass, a gift from him to me, and walked out slamming the door behind him. I left the broken vase on the floor for 3 days.

When I swept the sharp blue shards away and cut myself, I sucked on the blood angrily and made a vow to be independent for life. My resolve strengthened when a year later, I heard he got married to a mutual friend of ours. I read so much about blue jays for a span of 2 weeks; I felt that I had to for closure.

Then I chose to forget everything I learned about them. I learned to forget how these brilliant blue birds scared off other darling small birds from their nests and birdfeeders by mimicking the screeches of red-tailed hawks. They even used the same screech to fool the hawks themselves and feed on their food, or just to irritate them without a purpose.

They were restless, conniving, hyper, over-protective and paranoid creatures. They were commonly thought of as striking and colorful, but their displeasing presence trumped their beauty for those who cared to watch them for hours.

After those two weeks of senseless self-sabotage using the study of pretty blue jay birds as validation, I remained for the rest of my many years as an enabler to countless women whose lives needed guided empowering, and a confidante to many wonderful friends whose occasional superficiality needed tactful avoiding.

I did not regret any choice I made, except for one, but I don’t know how to put this regret into words. It has something to do with life rolling on through one tunnel, and before knowing it, it is on its way to being retired and essentially forgotten. It’s a universal regret, by the way.

A few months after my retirement date took effect and with it the gravity of time and its brevity, I received a phone call from an old friend, whom I forced myself to be reminded of as the wife of the birdwatcher. Her voice was frail yet edgy, her greeting was cold. She asked me for my address to send me what the birdwatcher had left for me before he died from a severe case of glaucoma.

As she explained his ironic death and her utter confusion when she found the letter with instructions for it in the will, I covered the speaker of the phone and vomited strange blue-ish liquids that were symptoms of what I later discovered was damage to my intestinal wall. The doctors could not tell me why the bile that purged from my body had a pale cobalt blue color. But I had a faint idea that it may have been the birdwatcher’s spirit leaving me.

The day on which my diagnosis was final – does it matter what life sentence it stated? Of course not. On that day, the letter from my birdwatcher’s wife arrived. He left me an open flight ticket to Alberta, Canada, and a paid-for invitation to a bird-watching retreat with the title: “The True Story of the Blue Jay & the Red-Tailed Hawk”

With it, was a folded white sheet of paper with his childish timeless handwriting: “Turns out that ultimately, even though blue jays are shrewd and mean with intelligence, they are the main saviors of the forest. The life of the forest could not be sustained without their mockery.” He didn’t feel a need to sign it.

The envelope, which was in the other envelope it came in, was wrinkled, timeworn, and dated fifteen years ago from that day. I knew enough about blue jays to know what his note meant, and I knew even more about living with lies to reassure his wife that the letter was insignificant. I threw away the ticket and invitation, but I kept the note that was never sent. I lived with those unsaid words.

I traveled to other places besides Canada, from which I collected anything that had a symbol of a blue jay. Magnets, crystal sculptures, ceramic bowls, candleholders, blue jay shaped soaps, meditation CD’s with the jay-jaying of blue jays… I became a mad blue jay lady who lived off a ghost of a hawk. Once my shelves and walls were full of blue jays with sapphire wings taking flight, I stopped vomiting blue bile and my body started to heal. I stayed alive longer than expected, almost two decades more.

On the sunset during which I died, seventeen years after my retirement and my medical diagnosis, I was sitting at home in my garden finally vanishing in my challenged organs after years of negotiating peace with them. Just as I was beginning to wheel my chair back into my house, a huge hawk with a tag on his leg sat on the branch of the Neem tree in my garden.

The hawk stared at me with his sharp eyes, screeching with a call of accusation. What an unpleasant sound it made. I immediately remembered my birdwatcher lover after years of restraining the thought of him within the blue jay elements in my home. I said out loud to the hawk, “I am a blue jay! I didn’t need to go Canada to watch your birds for confirmation! I AM A BLUE JAY!”

The hawk stopped his screeching, and stared at me intensely, he suddenly darted his gaze to a ruffle of bluish feathers that appeared from nowhere and resided on the armrest of my chair, the trendy blue mullet on its head protruding angrily with swag, screeching just like the hawk but louder and more frantically.

The blue jay – it was a she, and the hawk was a he, because it suits my story best and not because it was a biological fact – the blue jay hopped, she dove, and she rested again to prepare for another fuming dive towards – and suddenly away from – the enormous hawk.

Why wasn’t this pretty blue bird jay-jaying? Why wasn’t she singing with a wheedle-toodle-doo? More importantly, why wasn’t she escaping her predator?

The hawk looked pleased with – was that a smirk? Yes, a satisfied self-indulgent arrogance that I could not help but scowl at. He jutted his head forward and lunged deep within the branches of the tree for a few seconds and right back out, swiping straight towards the blue jay!

Call it divine intervention if you will, but I took the hawk’s blue feast by her wings and swung her behind my wheelchair for protection. The hawk fluttered his large wings in a static position that came even to my face, challenging me with a few squawks, studying me with indignation, and then falling silent.

I leaned backwards with astonishment from that deafening accusatory shriek; I must have done it with all my weight because my wheelchair tipped to one side and as it did, my head smashed against the Greek-blue pot that was, on that specific day, misplaced by my gardener. I heard a crack in my spine – or was it my neck? – I was knocked out of breath. My lungs were gasping for air, but my spirit was peacefully watching what the hawk would do next, oblivious to my fall.

The hawk did nothing. He held his static position above me with an enraged flap to his wings, while the blue jay struggled in my physically weakening grip, screeching like the hawk, whose perplexing silence, I was certain, was just to prove a point. But since I was unquestionably physically dying, my hold of the blue bird let loose and she eventually managed to break free from my fingers as the hawk dove with vigour right behind her!

The birds disappeared among the branches – swishes and swooshes – a bit of blue and lots of brown. They disturbed the leaves that fell and dwindled. That’s when I stopped trying to live. As my soul or spirit, or whatever you want to call ‘that’, was watching the strange angle of my body laid like a disfigured woman from a Picasso painting, I was somehow also able to feel what the hawk and blue jay were feeling while they did what they were doing, as if I was costumed with their spirits.

The blue jay was a few trees away on what seemed to be the hawk’s nest. She was wildly and hysterically pecking her beak on what seemed to be the hawk’s eggs, and when they were good and cracked, she screeched with victory before she flew away. She nestled on another tree to jay-jay by her nest and shelter three small blue eggs.

I felt her potency, her maternal madness and impracticality. In me burnt a sense of murderous revenge that I understood and forgave the blue jay for.

The hawk, on the other hand, was starting to feed on my open wound; his jabs were graceful and necessary for his survival, they were far from vengeful. It seemed that he no longer had anything to protect, but how did he know that if he hadn’t gone to see his nest?

I was out of my body by then, so I knew that he knew that the blue jay cracked his eggs for no reason other than her presumption that he would feed on hers. After all, he is the glorious predator, it is his dignified depiction on the very first pages in every textbook written about the bird kingdom.

He knew that the blue jay had to do what she had to do. It was their magnificent blue remnants that we often spotted beneath cracked dead leaves, not the remnants of the mighty hawks. I felt the nodding of the hawk’s surrendering pain nudging at my heart.

I was humbled by his compromise in letting the blue jay go. Each time his beak dug in my open wound, I felt that nodding nudge where I should not have felt it. It connected us. We both started nodding with surrendering pain. I became conscious of my reaction: what I thought was my divine intervention, was in reality my possession over nature, and what ultimately led to the demise of this hawk.

The autopsy said that I was dead before my head hit the blue pot. The gardener was not to blame. Death is not this simple and dreary, people. Without meaning to, a hawk provoked me to tip my wheelchair over, while I tried to protect his prey from his unquestionable superiority. But it was not only a pretty blue jay that the hawk was after; he was after a blue jay that was determined to steal his glory.

Isn’t it such an impalpable, granular, fine line for a blue jay? Between possessing a pure existence with a wheedle-toodle-doo, and demonstrating the intelligent intentions of fighting to be a hawk? Between being simply just gorgeous, and becoming an egotistic nuisance? Between fighting independently, and perishing utterly alone? Between being a predator, and becoming the predator’s prey? Such a bare thread for a line!

No, I did not die from natural causes; perhaps it’s better if we say that I died a wild death belonging to nature. I perished like a blue jay, loud with a mimic of a hawk’s squawk.

For the ones who risked flying solo like me, it is not bizarre for the profound purpose of our entire life to be reduced to a mere animation, a symbol. It can be as random as a passing transitory memory of a misunderstood blue bird, superfluous in her possession of the notion of survival.

I was very often found alone, but that last time I was found this way no one knew the real story of my death: the true story of the blue jay and the red-tailed hawk. I was murdered by birds of a love withheld from manifestation, flying and prevailing purely in the mind.

Some of us are most splendid in our aloneness. We would otherwise not be idolized as magnificent blue jays, imagined, worshipped and watched for a lifetime. We spread our wings with a pride so impressively lonely from being unbent.

Passersby spot our blueness beneath dead cracked leaves days later. They would never believe that our indigo spirit could have ever been ferocious when they find us stiff like that. Oh but we are!

Without our mocking ferociousness and without us pretending to be what we are so very not, the hawk’s enchanting forest would be a color less blue, a shade less brilliant, a soul less potent, and a fading wilderness depleted from a ravenous hunger for life.

Beisan A. Alshafei

June 5th, 2019