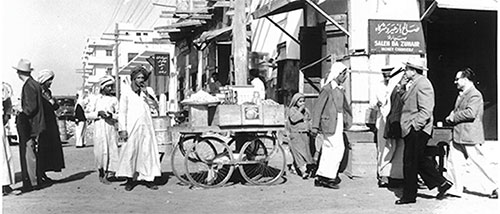

Once, upon a waning crescent moon during a spring in Khobar, Saudi Arabia, two apricot sellers wheeled their wooden carts down a long sandy curb outside of the market, a few hundred meters apart from each other. As the sun was packing to take its leave for the day, and so were the other market stalls being packed up for closing, those two brought their short-seasoned apricots to this curb where soon, the men will be walking past to the mosque for the evening prayers and the expensive scarce sweet apricots will be exclusively viewed and hopefully sold during that time.

That day, the younger seller passed the older seller a cold, bitter greeting, and the elderly responded with a nod of his head and a toothless smile, as was the usual protocol in the short two weeks when apricots are their sweetest. The younger seller had to initiate the greeting because it was custom; not going through with it despite the severe temptation to skip it was out of the question, due to honour code and all. He didn’t want to be this irritated, but he just could not understand how he, a young educated man with an ability to speak four languages and successfully manage two of his dad’s shops, one a tailor and the other a small radio repair studio, was not able to sell off even a quarter of the apricots that the older fruit seller sold further down the street. He once even sent his little brother to buy a couple of apricots from his competitor’s stall to taste if they were sweeter, but no! Surely, his own apricots were slightly sweeter and even bigger in size than his competitor’s!

Every afternoon during this apricot season, this young apricot seller would practice on widening his smile (for his facial features were naturally genetically serious). And after his siesta, when his father and older brothers were out of the house and his mother was busy in the kitchen, he would practice a tune that sings: “APRICOTS FOR LESS MONEY”, or something along those lines, for unlike the senior competitor, he was highly educated and could play with numbers to lure people to buy more apricots at a discount. But still, the toothless apricot seller, even with the unattractive aging smile, was able to sell almost all of the apricots on his stall, while he, the younger smarter one, wheeled a semi-full stall home and painful cheek muscles from smiling too hard. He had never faced such competition in his life, even though everything else he had ever marketed for sale was also expertly marketed and sold by at least two other families in this small neighbourhood in Khobar. Every day, he watched people leave the mosque, chatting with each other, most of which seemed oblivious to his voice and his price offers, only to stop abruptly to buy apricots from the stall further down. Save for the familiar few with bad legs that could not walk the extra couple hundred meters to that stall rather than his.

One of those people who passed his stall nonchalantly daily was my twelve-year-old father; shuffling his feet behind his father to pick up fresh hot bread from the baker every evening. He wondered how the apricots tasted; their smooth yellow skin had a rosy tint that signified how sweet they must be. And this seller was yelling out discounted prices every day. He made a sprint to catch up to his dad, a few steps ahead of him, and pointed to the first stall, “Yuba (dad), can you buy us some apricots? He has an offer on a kilo”. He received no response from his father, so he shrugged and walked on.

They reached the second stall of apricots, and now my father’s brother nudged my father and said, “I’d rather have apricots than bread, ask Yuba again”, but my father did not want to ask again, because this seller did not even have an attractive offer on the apricots, it was unlikely he’d receive a response from his father let alone convince him to replace hearty bread with sweet apricots as a compliment to the lentil soup being prepared by their mother and sisters for dinner.

Except, to both of the boys’ surprise, their father stopped by this second stall, picked up an apricot and brought it to his nose, he breathed it in, smiled and bought a kilo of them! My father, being the sensitive intuitive man he always was and still is, looked behind his shoulder to the other stand and noticed the younger seller with the cheaper apricots shake his head at his blushing fruits as he indignantly packed his apricots away. He turned to tap his father’s shoulder, and standing on his tiptoes he whispered discretely in his ear as to not insult this kind-looking toothless seller, “Yuba, the stall right by the mosque had a better offer on a kilo”. His father shook his head to brush the whisper off of his ear as if it was a noisy mosquito, and ignored his son with his smile slightly fainter, but still trapped in his lips. So my father shrugged again, and walked on home after the toothless happy man was paid.

On the way home, my father asked, “Why didn’t you get the cheaper apricots, Yuba?” And his father responded, “I don’t know. The second stall had better apricots I think”. But that was not true, because he was sure that his father did not even bat an eye to the apricots on that stall nearer to the mosque! The next day, and what was to be the last day of the rare sweet apricot season with the coming of the New Moon, my father decided to pay attention to the distinction between the two stalls. Earlier on that afternoon, he noted to himself how they both marketed their apricots with a welcoming singsong voice and fairly friendly faces, but one was seemingly better than the other. Was it because one was old and toothless and people pitied him? No. It could be counter-argued that the younger one was a hard-worker and needed the money more. What was it?

So there they were the next day, my father, his younger brother and their father, walking the walk from mosque to home, passing the first stall.

“HALF PRICE FOR TWO KILOS! SWEET AND SOFT! TASTES LIKE PURE SUGAR! HEAVENLY!” The young seller’s voice boomed to the passersby, very few of which stopped for today’s more attractive offer.

Further down the street, he could hear the older seller’s singsong voice too but couldn’t make out what he was saying. Most probably, he thought, it had to be something about apricots, and the price without an offer. My father was so eager to know the secret. But when he got to the second stall, this is what he heard instead of numbers and excellence of ripe taste.

“Bring joy to your children’s hearts! BRING JOYYYY TO THEIR HEARTS!” The older seller’s voice silvered through the sunset to the passersby, many of which stopped for this moment of truth and brought plenty of apricots.

Was it because he was wiser and nearer in age to the pure original old notion of “exchange of reward” that he was more successful? Maybe. Maybe as a parent and procreator, he understood that impulsive buying for people you love comes from the emotional heart and not the logical head. Saving an extra coin or two in your pocket is not as rewarding as spending them to bring joy. Surely, all apricots bring joy. But one of the sellers reminded us of saving money, and the other reminded us of spending love. One seller’s goal was to sell more sweetness, and the other seller’s goal was to feed more sweetness. One stall’s customers had a heavier wallet and an indifferent heart, while the other stall’s customers had a lighter wallet and a much fuller heart.

My father told me this story back in 2002 when I was about to leave home for college. I told him, with shame, that I would not follow his path in studying biological medicine and would rather major in international marketing. (I regret that decision today, but that’s a whole other story). Instead of being disappointed, his gentle eyes lit up! “You will learn so much about the brain, and the heart! Emotional patterns… psychology… perceptions… and setting intentions! It will be fun. Good luck. Do good.”

Perhaps those emotional apricot buyers, who bought the more expensive apricots from the toothless man preaching joy, are reckless. In fact, I doubt they made much money in their lifetime. But as a result, they had so much less to lose, and I would place a double bet that they each had more time to simply bring joy to people’s heart. This is surely a failed attempt at a Malcolm Gladwell marketing story. But it has a moral or two, after all. One: If you cannot bring priceless joy to hearts in giving what you have to offer, then you might as well not waste your time and offer it at all; I have found that this applies to every nook and cranny in life. And two: The best of joys can never be economically or numerically quantified, just as love can never be scientifically formulated and measured.

Beisan A. Alshafei

February 4th, 2019